|

|

|

The B.E.Ry. during the years of the Fair Haven and Westville

|

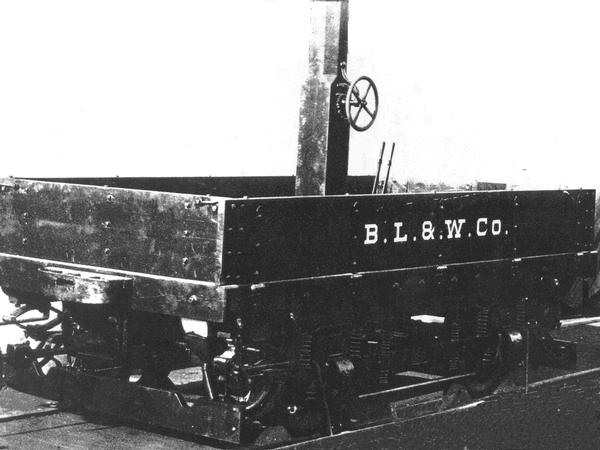

| Fair Haven and Westville single-truck closed car #71 has derailed on Harbor Street, Branford. The car was built by J.M. Jones in 1895 and was equipped with a Bemis truck, two G.E. 800 motors and two K-2 controllers. In 1915 it and car #70 were used by the Connecticut Company to build an experimental center-entrance car (#1605), which was finally scrapped June 6, 1929. Mason Foote Smith photo., Branford Hist. Society coll. |

Branford Awakes

|

Within weeks of the opening of the Branford line, newspapers

recognized the impact which the line was already making on

the lives of Branford residents. The New Haven Register, on

Friday, August 31st 1900, notes:

...many pleasant little reminiscences were told of primitive

Branford, when the place enjoyed its appellation of ``Sleepy

Old Branford.´´ Many of these old friends had left the town

before the dawn of its new era which has brought electric

lights, telephones, water systems, and last, and best just

at present, because new, the electric road. Branford's Rip Van

Winkle condition has passed into history, and now the old place is

very much awake.

Just a few days earlier, the Register commented on the growing

shore resort business:

The roasting atmosphere of yesterday, which was nearly as hot

as on that hottest of Saturday's, August 11, drove thousands

of people to the shores and the cool places in the neighboring

countryside. ...

The new Branford line was well patronized, fully 4,000 passengers

taking the ride down through Short and Double Beach to Branford

Point and Branford.

The service given by the trolley companies was extremely good

all day long...Two cars were kept going all the time to the

East Haven green with passengers for the Branford line, and the transfer

made at the green under the management of a very competent starter.

The Branford line over the new route was well patronized, and the beauties

of the new route thoroughly investigated. The line provides some

of the finest scenery along the local shores and will undoubtedly be

a popular line when it is known. The reduction of fare to East Haven

to 5 cents makes the ride but 15 cents.

While there are conflicting accounts, most newspaper evidence supports

the theory that the permanent connection between the Branford line and

the rest of the Fair Haven and Westville (FH&W) system at the East Haven

Green was made during the week of September 3rd, 1900, when two

turnouts were placed in service at Hemingway Avenue and River Street.

New Cars

The Branford Opinion of December 1, 1900 reported a minor

derailment:

The car which is due to leave the green at 1:24 was derailed at the

top of the hill near Corporal Sullivan's residence {Harbor Street}

yesterday. The car was coming toward Branford, and when it had nearly

reached the top of the hill it left the rail and ran across the road

nearly to the fence before it stopped. Mason F. Smith was the only passenger

on board the car, and he and the conductor were thrown together in

the center of the car. Neither were injured. The wrecker came out from

New Haven and got the car back on the rail. No cause for the accident

could be found.

The lone passenger, Mason Foote Smith, was an avid shutterbug

employed by the Yale Observatory;

he took several

shots of this incident which have survived. Indeed, he took

many photographs of the early days of the Branford line and might

be considered the Branford Electric Railway's first railfan.

The derailed car, Fair Haven and Westville (FH&W) #71, was

a single-truck closed car typical of the type assigned to the line

during the winter months. The same newspaper issue describes the new cars

which would soon arrive from J.G. Brill:

They will be forty feet long, wider than the general run of cars,

and vestibuled...Ten windows of plate glass made as large as the

sides of the car will render the car as light as possible in the

day time, while twenty electric lights, double the number in an

ordinary car, will make it likewise light at night. The cars will

be finished in the best mahogany, and its seats with their backs will

be provided with springs and upholstered in the finest Wilton carpet.

The seats will be arranged nine on each side of the aisle with

one in each corner, and the cars will seat forty-four people.

Each car will be fitted also with four electric motors, which is double

the number on other cars.

The new closed cars would be numbered 124-127. Car 125 entered

service first, on December 22nd, and the others followed shortly

thereafter. During the summer of 1901, the single-truck open cars

were back on the line to provide air-conditioning. An additional

order of cars, 146-151, similar to the 124-127 group, was delivered

in 1902.

|

| This photo of car 127, which was involved in the fatal wreck of 1902, is believed to be taken shortly after delivery in the winter of 1901, at Main and Laurel Streets. St. Mary's Church is in the background. It was part of a group of cars (124-127) which was equipped with Brill 27G trucks, four G.E. 52 motors, two K-12 controllers and an Allis-Chalmers air brake system. The group was renumbered 581-584 and sent to the Torrington division in 1915, and sold in 1929. Mason Foote Smith photo., Branford Hist. Society. coll. |

Trolley power for the line was not generated by the

Branford Lighting and Water Company's plant in Branford. Rather,

it was supplied from the FH&W generating station ``B´´ located

at Ferry Street in New Haven. During periods of heavy usage,

the voltage at the Branford end of the line sagged heavily,

causing delays in service especially during the summer of 1901.

Additional generating capacity and improved feeder cables were

deployed to address the problem.

The New Haven Register made the following amusing observation in 1901:

Quite a little annoyance is caused to strangers Summering at Short

Beach who are not familiar with the fact that all trolley cars must

pass through Short Beach to reach Branford. Many have gotten badly

fooled in New Haven anxiously awaiting the coming of the car that

never comes labeled Short Beach....

Although there were scattered reports of outages and delays,

in general public opinion of the new Branford line was quite

high during these early years and ridership was very strong.

The Wreck of 1902

On warm summer evenings, it was not uncommon for double-headers and

triple-headers to run back from Branford, carrying throngs of

homeward-bound beach and resort patrons.

On Saturday, the 26th of July 1902, two extra

cars were dispatched for picnic-goers at Double Beach. They delayed

the regular 6:48 P.M. car from the Branford Green by about six minutes.

Most of the Branford line in 1902 was single-track with passing sidings.

One of the sidings where opposing cars met was known as the

``gravel pit switch´´. It was located just west of the ``Riverside´´

S-curve, at approximately the location we today call ``Beacon´´.

The regular car from Branford, #127, was operated by Motorman

Peter Sture Lindstrom.

Only 25 years old, Lindstrom was already an experienced and respected

man on the FH&W. His conductor that day was George J. Hugo.

At the gravel pit switch, car 127 was

scheduled to pass the opposing car at 7:18 P.M. Motorman Joseph Smith,

operating eastbound (Branford-bound) car 145

(an oddball single-truck closed car built

in 1902), brought his car to the switch and waited

in the twilight. (Sunset in Branford was at 7:16 PM. Daylight Savings

Time would not be invented until 1918).

Smith had been working as a motorman for only three months,

and had just been assigned to the Branford route three days

earlier. His conductor, W.W. Peterkin, had been working for

the FH&W but five weeks.

The first westbound special car passed. Its motorman, Martin Marlin,

waved his hand, indicating that cars were following. Motorman Smith

received this signal. However, he later stated, he expected a number

of fingers to be outstretched, corresponding to the number of following

cars. This, he claimed, was customary procedure among motormen and

conductors. Knowing only that there was

at least one car following, Motorman Smith waited at the switch.

Quickly, the second special car came into sight. It, like the first,

was almost certainly a single-truck open car, as these were used

at the time for

summer extras, however the exact car numbers are not known. Motorman

Smith would later testify that the motorman of the second car, J.L.

Overlander, did not signal. Unsure, Smith continued to wait.

A minute or two went by. Conductor Peterkin pulled the bell cord

twice, signaling Smith to proceed. When the car did not move, Peterkin

went to the forward vestibule. Although Peterkin, stationed in the rear

of the car, had not been able to see the signals of the opposing motormen,

he advocated proceeding slowly. He returned to the rear vestibule and

rang the bell again.

Car 145 started forward and entered the curve. Car 127, moving downhill

at a considerable speed and expecting to find a clear track, came sweeping

into view. The darkness and heavy vegetation on Beacon Hill contributed

to an estimated visibility of 25 feet. There was scarcely time to shut

off power and crank on the brakes before the two cars met with a

great crash.

Car 145 climbed and rode over the vestibule of car 127, pinning Lindstrom.

Motorman Smith received several gashes on the head. There were a total

of 19 passenger injuries, all of which were comparitively minor. An East

Haven boy of 12, Leslie Augur,

although badly cut, freed himself from the wreckage and ran to East Haven

to summon help. A doctor from East Haven arrived about a half hour

after the accident. Additional doctors came via trolley from Branford.

A repair trolley was dispatched from New Haven and en route collided

with an ice wagon in East Haven, evidently causing no injury. The most

seriously injured were taken via trolley to New Haven Hospital.

Motorman Lindstrom had lost a great deal of blood as both his legs were

crushed. With modern medicine, he probably would have recovered.

Doctors amputated his legs in an effort to save his life, but he died

shortly after midnight, minutes after his sister arrived at the hospital.

The funeral for Lindstrom was held several days later at the Swedish

Lutheran Church at 149 St. John Street.

The Reverend A.J. Enstan presided. The

pallbearers were fellow FH&W employees: Starter J. Quinn, Motormen

George Kelly, J. Hogan and N. Simon, and Conductors E. Priest

and A. Beckwith. Lindstrom, who was born on March 14, 1877, was survived

by his parents, three brothers and three sisters, most of whom resided

in Sweden. One brother, Oscar, lived locally, as did his sister

Mrs. J.E. Sundblad, with whom Motorman Lindstrom resided at #15 Tilton Street.

The FH&W donated floral arrangements and an undisclosed sum of money

to the Lindstrom family. Times certainly have changed in 100 years, as

there was no mention in the newspapers of lawsuits by the family or any

of the passengers!

Coroner Eli Mix opened an inquiry into Lindstrom's death. Motorman Smith

was taken into custody on Sunday the 27th and

released that evening on $1,500 bond.

Coroner Mix released his findings on Thursday the 29th.

He attributed fault for the

accident solely to Motorman Smith and Conductor Peterkin. He accepted

the testimony of the crew of the second car, Motorman Overlander and

Conductor Terrill, that Overlander had held up his hand to signal that

yet another car was following. (It should be noted that earlier newspaper

accounts of the incident stated that Overlander was the first motorman

and Marlin was the second).

Motorman Smith denied receiving the second car's signal, and at least

one witness aboard car 145 agreed with Smith. The Coroner included

in his report the suspicion of some of the passengers aboard car 145

that Smith was intoxicated. The truth will never be

known. However, as Coroner Mix pointed out in his report, the crew of

car 145 should have known that the regular car had not yet passed, as

the two special cars were single-truck opens, while the regular cars

on the Branford line at this time were the double-truck closed cars.

The Coroner also recommended that the FH&W use a system of flags and

lanterns on the cars in place of hand signals, and noted that such was

already the practice on other divisions of the FH&W (perhaps those

former Winchester Avenue routes which had been acquired in 1901).

He faulted the

Branford Lighting and Water Co., owner of the

line itself, for not maintaining the brush in

the curve, and strongly recommended double-tracking the entire line.

He urged that the heavy double-truck cars,

which weighed in at 15 tons, be equipped with air brakes. (This

is a curious statement, as all other surviving evidence indicates that

Car 127 was delivered with air brakes.) Finally,

he commented on the design of the closed vestibule cars, which

had a curtain that

closed off the vestibule at night to block the reflection of the electric

bulbs which would otherwise diminish the motorman's view. He stated that:

If the motorman should be attacked with heart disease, or should faint,

where would the passengers be in a few minutes?...the car would run

along without the passengers knowing that anything was the matter....

I think if an arrangement could be made so that the people on the car

could see the motorman, it would be a great safeguard to the public.

His concerns would be answered decades later by the invention of the

``safety car´´.

There is no record of any criminal trial of Smith or Peterkin, and

rumors were that they fled the area to avoid prosecution. Cars 127

and 145, though badly damaged, were repaired and returned to passenger

service.

A Strike

At the same time that news of the collision was being reported, there

were accounts of some labor unrest in the FH&W Co. On

Thursday August 7th

a strike was called. The principal issue was the discharge of several

employees. The men of the FH&W had formed a union, which now numbered

over 400, and they walked off the job at 3 A.M.

Although the strike, which lasted two days, was a minor note in the

history of the line, it affords the opportunity to examine how integral

the trolley had become to daily living.

The City of New Haven was paralyzed as its citizens scrambled

to get around by bicycle, horse or on foot. Short Beach was particularly

hard-hit, just at the height of the summer recreation season. The New Haven

R.R. picked up considerable alternate traffic between the New Haven and Branford

stations.

Public sentiment was strongly in favor of the striking car crews, despite

the inconvenience. Much can be drawn from this simple fact. To the

average person on the street in 1902, a trolley worker was a comrade,

a fellow man putting in an honest day's work for a honest day's pay.

On the branch lines in particular, such as the Branford line, customers

came to know the car crews personally. They might ride a particular

run several times each work week. The fare was handed to the conductor

personally, not dropped into an anonymous farebox, and the conductor

surely came to know the names of his customers.

The Fair Haven and Westville, on the other hand, was a large monopoly

corporation.

As detailed in the first installment of this series, through a series

of mergers, acquisitions and contracts they came to control all of the

street railways in the New Haven area, the final piece of the puzzle

falling into place in 1901 when the FH&W acquired controlling interest in

the Winchester Avenue Railway. The fare was more than adequate

to recover power, labor and materials costs and still deliver a healthy

profit. One could speculate that the July collision also fueled

an increasingly negative public opinion of the trolley company.

In 1903, proposals to extend the line to Stony Creek were defeated

in the legislature.

Double Tracking

As originally opened in 1900, the Branford Electric Railway was a single

track road, except for the 3-block segment in East Haven. Passing

sidings at several locations were provided. The July 1902 collision

put considerable pressure on BL&W to double-track the dangerous curves.

On August 23rd 1902, BL&W announced that

they would double-track Riverside curve, including replacement of the

Stony Creek Trestle. On December 19th it was reported that the

East Haven Trestle too was in the process of being replaced, and passengers

were forced to transfer across the old trestle. Chidsey Brothers

constructed the trestles and Blakeslee & Sons handled the roadbed and

track work. By January 2nd

1903, the double-tracking had been completed and both new trestles and a

new bridge over the Quarry railway were

in service. At this time the opportunity was taken to upgrade the original

track from 60 to 70 pound rail. The straight portion of the line between the

Stony Creek Trestle and Short Beach remained single-track until 1904.

The Coming of Consolidated

The economies of scale motivated much merger and acquisition activity

in the trolley industry after the turn of the century. The New Haven

market was no exception. By 1901, the Fair Haven and Westville

Company controlled the entire New Haven street railway system. Alas,

there's always a bigger fish!

The Consolidated Railway Company was the brainchild of C.S. Mellen, President

of the New York, New Haven and Hartford Railroad.

Trolley routes provided competition to the

mainline railroad business, and Mellen endeavored to build an empire

which would control all rail transportation. Starting in 1902, the

New Haven R.R. acquired a number of trolley operators' charters

and used the most liberal terms, found in the charter of the Thompson

Tramway Co. to incorporate a holding company, the Consolidated Railway Co.,

on May 18th, 1904.

Two days later, it acquired the FH&W

and assumed the operating agreement which was already in place between

the FH&W and the BL&W Co.

Consolidated desired to own the Branford line outright, however there

were difficulties in the negotiations as the BL&W Co. wanted to be bought

out whole. Consolidated had little interest in the electricity and

water aspect of the business. Agreement was reached on September 5th

1905:

Branford's lighting and water facilities and trolley line all

passed into the control of the Consolidated Railway company today as

a result of the special meeting of the stockholders which was held

this morning in the general offices of the New York, New Haven &

Hartford Railroad company.

...

The price paid for the road is said to have been about par, the payment

having been made in the 4 per cent debentures of the Consolidated

Railway Company. It is said that the stock issue of the road is

about $300,000, while there is a bond issue of $350,000...

The sale is very satisfactory to the old stockholders. By it the

New Haven road gets the trolley from East Haven to Branford. It wanted

to buy the trolley without the water company or electric lighting

system, but that could not be arranged. Selling water and electricity

is new business for the Consolidated road, but the right to

engage in these enterprises was obtained by its amended charter.

On September 26th 1905, the BL&W Co. received a payment of $225,000

from Consolidated ``for all the contracts, property rights, powers, privileges

and franchises.´´ Thus was the corporate end of the

Branford Lighting and Water Company, and the end of local ownership

and control of Branford's trolley.

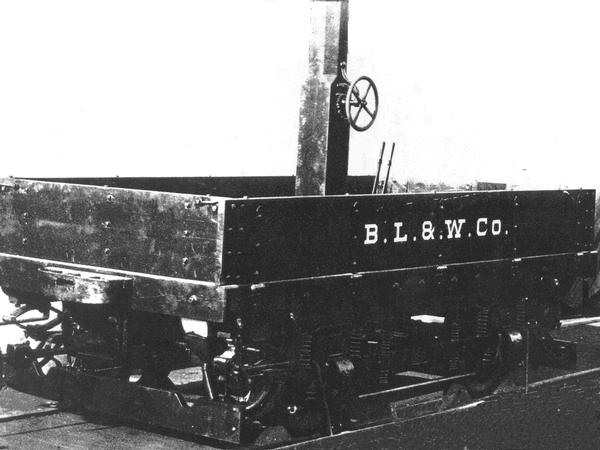

|

| The only piece of rolling stock owned by Branford Lighting and Water Company was this 14' single-truck utility motor car. It was ordered from Brill in October 1903, and was probably housed at a small facility in the ``Red Barn´´ area near Stannard Avenue. Motors, controller and pole were mounted by New England Construction for BL&W. The Connecticut Company later scrapped the body but reused the truck to construct ConnCo flat motor #0116. |

Thanks to James M. West, Prof. George Baehr, Jane Bouley of the

Branford Historical Society and William B. Young

for contributing to this article, and to the late Dick Fletcher for his

research. In the next installment: Murder on the

tracks! The Stony Creek extension, and the Branford line in the heyday

of the Connecticut Company.