|

|

|

The Heyday of the Branford Elec. Ry.

The Consolidated Era

The acquisition by the Consolidated Railway of the Fair Haven and

Westville in 1904, and of the Branford Lighting and Water Company in

1905, marked the end of the Branford trolley as a local affair. Now

the line would be managed from afar, as the Branford route

of the New Haven Division.

The Consolidated Railway was a holding company for the New York, New Haven

and Hartford Rail Road, which since 1902 had been acquiring various

street railways. Consolidated was indeed a fitting name. Under the

direction of C.S. Mellen, President of the New Haven, Consolidated was

a carnivorous entity that swallowed up smaller properties whole, often

paying entirely too much for them. In particular, the terms of the

999-year lease in 1906 of a major competitor, The Connecticut

Railway & Lighting Company, would prove to be

an albatross in later years.

Mr. Mellen, it has been said,

was an empire-builder set on controlling all forms of mechanized transportation

in and about Connecticut. Perhaps it was with this in mind that in 1907

the company changed its name from the mundane ``Consolidated'' to the

imposing and all-inclusive handle of ``The Connecticut Company'', or

``ConnCo'' as it became known in the trade, and it is under this name that

service on the Branford trolley would continue until 1947.

|

To Stony Creek

|

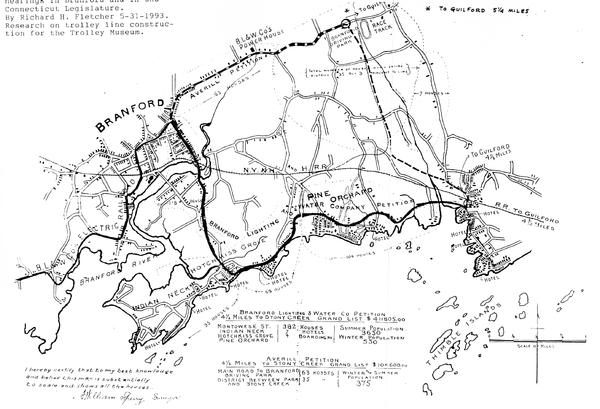

| This map, drawn in 1903 by BL&W engineer A.W. Sperry, was discovered by Dick Fletcher in his research. The map compares the two proposed routes for the Short Beach extension. The BL&W route eventually prevailed, though there were some differences in alignment between this map and what was constructed. |

Extension of the Branford line to Stony Creek, in the southeast corner of

the town of Branford, had been proposed in 1903 by the BL&W Co. While

they favored a route that headed due south from the Branford Green

and followed the shore out to Stony Creek, another proposal, backed by

the town, would have the line continue along Main Street,

beyond the BL&W Co power station, near the present-day Mill Plain Road,

(this point was to be the original terminus of the line, as proposed in the

1897 charter, though when built the line stopped some 2 miles sooner), and

then south into Pine Orchard and on east to Stony Creek.

Both proposals were defeated during political maneuvering in the State

Legislature and the matter was not revisited until 1905, at which time

the BL&W route was approved. However, ownership of BL&W

was in the process of changing hands.

The Stony Creek extension would begin in 1906, under Consolidated.

5½ miles of single track and several passing sidings were built,

with some considerable engineering work required in

places. The construction is covered well in the book

Along Branford Shore, by Richard Fletcher and James West.

The line to Stony Creek was opened on Thursday, June 27th 1907.

A 48 minute headway was maintained in conjunction with the existing

24 minute Branford schedule; alternate cars either terminated at the Branford

Green or ran through to Stony Creek.

|

| Consolidated car 509 (renumbered 862 in 1915) as photographed by Mason Foote Smith shortly after delivery. Location is believed to be Main and Laurel Streets. Courtesy Branford Hist. Soc. |

New Cars

The Consolidated Company placed an order with the Jewett Car Co. in 1904

for 15 wooden suburban-style cars. They would

be numbered 185-199 and

assigned to the New Haven Division where, along with cars 501-515 from

a larger 25 car order placed in 1905 with Wason, they formed the closed car

fleet for the suburban lines. The new cars

displaced the Brill city-style cars (124-132 ordered in 1900,

145-151 ordered in 1901 and 153-163 ordered in 1902).

These new suburban cars came with Taylor SB trucks, K28 control and

four Westinghouse #68 motors, each

delivering 35 hp. They were geared for the quick running often

found on the suburban private right-of-way sections, with a top speed of

approximately 40 M.P.H. By 1908, ConnCo had substituted Standard O-50

trucks and either General Electric #80 or Westinghouse #101 motors.

Some cars were later outfitted

with K35 or K6 control.

Overhead luggage racks provided storage for

those larger parcels -- perhaps a picnic lunch and a blanket headed for

a day out at one of the beaches or hotel resorts of the Branford shore.

Because the Consolidated / Connecticut Company was an amalgam of formerly

distinct railways, car numbers were not unique across the state-wide system.

ConnCo corrected this in 1915 by re-numbering all of their cars sequentially

by age.

Cars 185-199 became 767-781, while 501-515 became 854-868. Wearing these

second numbers, car 775 (formerly 193) still operates on the museum line

today, while car 865 (formerly 512) is being actively restored, the body

of 855 (formerly 502) is used as the East Haven Tourist Info Center,

and the body of 771 (formerly 189) is at Connecticut Trolley Museum.

Boom Times

The next decade would prove most prosperous for Branford and its trolley

line, the presence of which made the Branford shore line

an appealing place to operate hotels, cottages, boat houses and other

such summer attractions. During the season the Branford cars were

packed to the clerestories with passengers. So popular, in fact, were

the trolleys that local papers began to publish complaints

about the overcrowding.

In one letter to the editor, a Branford resident chided East Haveners,

who had their choice of either Momauguin or Branford cars to reach their

destination, for crowding onto the Branford cars and depriving Branford

residents of a seat or even the opportunity to squeeze in. He tactfully

suggested that perhaps it would be polite to wait for the East Haven

car which might be a minute or two away.

Another letter expressed frustration with Consolidated's handling of heavy

special-event crowds:

The notoriously parsimonious and inefficient management of

the Consolidated Railway culminated yesterday in its failure to

properly provide for the large number who planned to attend the

Branford Carnival. After every possible effort for several days to

secure a large number of passengers and every reason to expect them,

this non-progressing company provided in addition to its regular

cars, six small, antiquated cars worn to the last degree of safety and

with barely power enough to crawl over the curves and grades.

[Branford Opinion, Oct 4 1906]

Although obviously colored by anger, the description of Consolidated as a

``non-progressing'' company was accurate. Consolidated / ConnCo would

never be a cutting-edge trolley company. They were conservative and frugal,

a fact that would later work in the museum's favor in that many of the older

cars survived.

By 1906, Consolidated's order of 15 bench, double-truck open cars (such

as car 401 in the museum's collection) was coming in and they would

be assigned, as needed, to make extra service on the Branford line. By 1912,

a sufficient number of these large opens was on hand that four cars

would be regularly assigned to the Branford route. These

labor-intensive open cars began to be withdrawn from regular service

in the 1920s.

Murder on the Tracks?

On the foggy evening of January 21st, 1906, the motorman of the

Branford car struck what he initially thought to be a large sack laying

on the roadbed in the vicinity of Harbor Street. Mason Foote

Smith, our honorary first railfan of the Branford Electric Railway, was

on board the car, just as he was 6 years earlier when FH&W car 71

derailed in the same area. Smith and the motorman got out to investigate

and discovered that the car had struck a man. He was seen by the local

doctor and died shortly thereafter of his injuries. The victim, William

S. Schenck, was a pattern maker for one of Branford's largest employers,

the Malleable Iron Fittings Co.

Foul play was suspected. Witnesses said that Mr. Schenck had been involved

in a bar-room brawl earlier in the evening, and that three men had

followed him out of the tavern. It was suspected that he was struck

unconscious and then placed on the track. New Haven County Coroner

Eli Mix ruled the death accidental and did not find foul play.

Townspeople remained skeptical.

A Spate of Accidents

A head-on collision occurred in the curvy private right-of-way section

of Double Beach on the afternoon of June 17th, 1909. The collision

involved a passenger car and a trolley express (parcel service) car.

There was apparently some confusion as to which car was supposed to take the

siding. There were a few serious injuries, but evidently no fatalities.

Later that year, on July 30th, there was a minor accident in the

Short Beach meadows (now part of the museum line):

As the car was crossing through the long stretch of meadow at

a high rate of speed, the conductor slipped from the running board.

A passenger pulled the bell cord, and the motorman backed the car. The

conductor was picked up and seemed badly hurt. He was placed aboard

the next New Haven bound car. Another conductor was secured and

there was little delay.

Well, it certainly is a relief to know that there was little delay!

A more serious accident occurred on July 18th, 1910 with similarity

to the 1909 accident. A westbound trolley express car collided head-on with

a Stony Creek bound passenger car in Pine Orchard. Both cars were

traveling fast and were heavily damaged. The motorman of the passenger

car, William Baker, who had started as a horsecar driver in 1887,

was killed instantly. The crew of the trolley express car, motorman

Joseph Gorman and messenger Archibald Lynn, claimed that they had the

right of way and that the passenger car should have held in the siding,

which was quite some distance west of the accident scene.

Unlike the 1902 fatal collision near Johnson's Quarry, this accident

drew very little attention. There is no mention of a Coroner's

inquest. Thomas J. King, who had started on the Branford

line in 1902, was the conductor of the passenger car. Whatever

disciplinary action was taken against him is not known, but he would

go one to have a long career with the company, still working 45 years later

on the Branford line when it closed.

|

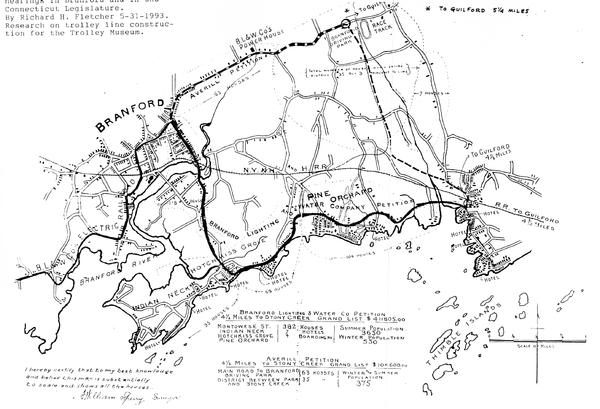

| Eastbound car 189 has derailed and slid off the track into the Long Island Sound at Granite Bay, Short Beach. The top view is looking east. The water in the foreground of the bottom (westward) view has since been filled in and houses constructed thereupon. photo: Priscilla Deibert Oliver coll., courtesy Branford Hist. Soc. |

The shore-hugging route of the Branford line would cause no end to

weather-related delays, particularly in the winter months. On

February 2nd 1915, with temperatures just around the freezing

mark, a winter storm created layers of ice, sleet, slush and snow

that crippled service in New Haven, particularly on the Branford line,

and made plowing difficult. There were numerous derailments resulting

from the iced flangeways, including an embarrassing incident in

Short Beach as car 189 came off the rails and slid into the Long Island

Sound. According to ConnCo manager Frank P. Harlan, the car body

had to be jacked off the trucks and dragged onto the side of the road

to clear the track. Branford and Stony Creek were effectively

isolated for several days, and with downed telephone lines too,

it must have seemed a throwback to the turn of the century.

Over the Hill

The word bus, which to many a trolley fan is of the four-letter variety,

first appears in the history of the Branford trolley in 1919, when

``Jitney'' (a contemporary slang term for a nickel coin) bus

service began between Branford and downtown New Haven via what is

now U.S. Route 1. Although unregulated Jitneys, cruising along trolley

routes and skimming passengers, were a major problem for many trolley

companies in the mid-teens, this does not appear to be the case on

the Branford line. This Jitney service was licensed. With a

½ hour schedule and a fare of 10¢ to East Haven and

20¢ to New Haven, this was an additional service for inland

passengers who were far away from the shore line trolley route.

Not to be outdone, the Connecticut Company began a bus service

on July 14th, 1921 that mirrored the Jitney's route, in fact,

the Jitney operator threatened to sue stating that ConnCo was infringing

on its franchise. A settlement was evidently reached. The ConnCo bus

began at East Main Street and North Branford Road, using the terminus

of the original charter of the Branford Electric Railway, and

continued through Branford, over Branford Hill, turning back at

the East Haven Green, where connection was available to the trolley.

ConnCo, finding that it was competing with itself by having a parallel

route, and finding ridership disappointing, discontinued this bus

service on November 15th, 1925.

There was one fatal bus accident

noted: On October 12th, 1921, a U.S. Army transport truck

carrying 20 soldiers from Camp Deven slid on the rain-slicked road

at Branford Hill and struck ConnCo bus #5. The bus, driven by

operator Harry Lee, was without passengers. 1 soldier was killed and

3 seriously injured, all of whom were sitting off the edge of the

transport truck and were crushed between it and the bus.

There was very little newspaper coverage of the Branford trolley in the 1920s,

meaning that service was most likely adequate and there were few complaints.

The peak years, though, were in the past, and ridership declined slowly

throughout the 1920s. Circa 1924, the 24/48 minute headway of the

Branford/Stony Creek line was cut back to 30/60.

In 1925, the Tomlinson drawbridge was rebuilt and viaducts were constructed

to cross the New Haven R.R. tracks. Subsequently, Lighthouse Point,

Momauguin and Branford cars ran from downtown New Haven via Water Street

and the Tomlinson

bridge, saving several minutes over the original Ferry Street route.

The End in Sight

The Branford Review, April 2nd, 1931, reported:

There is a well defined report that amounts to more than a rumor

that the Branford trolley line, among other suburban lines

of the Connecticut Company, may be abandoned in the not distant

future. This, while not confirmable, and while it may undoubtedly

be denied by officials of that company for diplomatic reasons, has

without doubt basis in fact, even if plans have not as matured to the

stage of action

The reason for the proposed, projected or hypothetical closing of

this line are many and multifold, but they concern chiefly the

financial return of the line in conjunction with that of other

suburban lines and their general relation to the entire Connecticut

Company system and the maintenance of its financial structure.

One of the chief causes of suburban trolley abandonment, say

authorities on street railway matters, is not the bus or other

public conveyance, but the private automobile. And against this

they cannot compete, neither can they devise any effective measure

of regulation. The private automobile, with the advent of universal

good roads travels everywhere, without any consideration given

by the owner of cost of upkeep, roadbed or maintenance; matters

which the trolley cannot ignore and exist. The private automobile

owner has a friendly habit of inviting neighbors, acquaintances

or entire strangers, who may be going in his direction to ride

along with him. This, whether it results disastrously for him

or not persists and increases with the result that it takes a large

portion of the natural passenger traffic away from the trolley and

puts a severe crimp in its revenue return.

...

It may all be a matter of evolution in transportation, but it comes as

a matter of regret to the "old timer" to see the "good old trolley

ride" or the "honeymoon days" going into the discard. To sit on the

front seat of the open car and veritably whiz through fields of

golden rod, with the cooling breezes gushing by one's

fevered brow on a hot night in "the good old summer time" -- those

were the good old days.

The story was confirmed two weeks later by J.K. Punderford, President

and General Manager of the Connecticut Company. Noting the decline

of the trolley to be a nationwide problem, Mr. Punderford predicted that

soon bus operation would cease to be profitable as well. Going further,

he mentioned that very few trains stopped anymore at the Branford station

of the New Haven R.R., and that the State highway department was contemplating

re-routing the ``State highway'' (U.S. 1) to the north of the town,

bypassing Branford (in fact this did come to pass when North Main Street

was constructed in 1932). He worried that Branford would become an

insignificant, isolated town.

Of course, the outcome was not quite as dire as predicted. Branford expanded

around the new roads, just as it had earlier expanded around the trolley line.

Gone, however, were the glory days of the shore resort business. By 1931,

the country had slipped into the Great Depression. The common man simply

did not have the leisure dollar to spend, and those that could afford

a vacation explored new and distant places in their automobiles. The Branford

trolley depended on heavy summer ridership to carry it over the lighter

winter months, and to finance the considerable cost of maintaining

the road which required frequent filling and grading. The newspaper

notes that ridership on the East Haven lines, though, was still fairly

good year-round.

The Rise of the Automobile

The biggest threat to the trolley was, indeed, the private automobile.

When the Branford line opened in 1900, the automobile was an experimental

oddity. Only a few thousand cars were produced in the entire United

States. Within a few years, mention of automobiles in the town began

to make the local papers, more as a rich man's curiosity than as a

rising trend.

1908 is popularly considered to be the watershed year of automotive

transportation, when Henry Ford introduced the

Model ``T'', and subsequently mass-production. Driving prices

down ten-fold, Ford made the automobile at last affordable

to the common man. After the Great War, automobile ownership began

to soar.

The automobile begat a shift in peoples' living patterns. Freed from

the constraints of the fixed route of the trolley, people began to spread

out and develop previously unsettled areas. Eventually, this would

create a vicious cycle. As people and businesses de-centralized, the

trolley seemed less effective as a means of transportation, and the

automobile became a necessity of suburban living.

This pattern was only just beginning, though, when ConnCo's

intentions of abandonment were announced in 1931. Of a more immediate

concern was the siphoning of trolley passengers by private automobile

drivers. At the time, road

capacity was more than ample for what was still a small number of cars,

by today's standards, and driving to New Haven must have been much

quicker and easier than taking the trolley.

The Branford Review was a staunch supporter of ConnCo in the face

of these trends. In urging legislation to curb private

autos picking up trolley passengers, an April 16th, 1931

editorial states:

...The business {trolley line} would pay for itself if the

company did not face the competition of the private car owner

in transporting passengers himself.

That this is done is well recognized. Many car owners transport

passengers, whether acquaintances or not. There are others, however,

who take into town or about town fellow workmen for a fixed

charge, at so much a week. This is not only unfair competition

but it is illegal. It may seem like good fellowship to do this,

but in all fairness is it?

A person who takes such passengers takes upon himself considerable

risk of financial loss and possible imprisonment in case of

accident or injury. In addition he causes a worthy business

enterprise to suffer to such an extent that it must close down

that business. This throws other workmen out of work adding to

unemployment, inconveniences those living along trolley lines,

brings loss to merchants who look to the trolley as a means of

regular transportation of customers and leaves a veritable wake

of evil in its trail.

The Trolley in the '30s

With increasing auto traffic, accidents began to rise as automobiles and

trolley cars learned to share the busy streets. On April 23rd,

1931, an automobile collided with a trolley car at Main and Kirkham

streets in Branford. Two passengers in the auto were injured, an un-named

girl and one Mrs. Sarah Kline, who reportedly sued ConnCo for $5,000.

On January 30th, 1932, Shelby Montroy, a resident of Lanphier Cove,

was arrested for reckless driving after he passed a trolley car on

the wrong side at Main Street and

Beacon Avenue, Branford, and struck a Miss Helen Gaffery of East Haven,

who had just alighted from the car. The woman was slightly injured.

There were several incidents in which a

pedestrian was fatally struck in the vicinity

of the private right of way between Double Beach and Brockett's Point.

On November 7th, 1933, Arthur C. Hills, a 66 year old piano tuner,

was killed while walking along the tracks at 1:22 P.M. Motorman David

Fitzgerald, operating a westbound car, saw Mr. Hills, slowed and sounded

his whistle. Mr. Hills turned and acknowledged the car, then inexplicably

crossed in front of it and was killed instantly.

In the same area two years prior,

on October 26th, 1931, an elderly woman,

Elizabeth Sondergeld (whose age was given as anywhere from 75 to 90),

was struck and killed at 8:15 in the evening. Witnesses said

that she had been riding in an automobile and was dropped off nearby,

and was probably trying to find her way home when she stepped in front

of motorman Richard Hannon's westbound car, number 865 (now

in the museum's collection). In both cases, a coroner's

inquest exonerated the motormen of any blame.

At some undetermined point between 1926 and 1931, ConnCo relocated a

crossover between the eastbound and westbound tracks. Previously, it

was located just west of the Quarry Trestle. It was moved out to the

straightaway in the Short Beach meadows. In conjunction with this, a dump

spur siding was built that branched off to the north of the right-of-way

into the marsh. Primarily small trash seems to have been dumped here.

There are stories of whole cars being scrapped out on the dump spur, but

they have not been substantiated. Some of the line poles in the siding still

stand today and can be seen while riding along the museum line.

The wooden cars on the Branford line were quite dated by the 1930s.

ConnCo had ordered 50 steel suburban cars, number in the 1900 series,

in 1919. After abandonment

of routes in Bridgeport and Waterbury, more of these cars were made

available to the New Haven division, where they displaced the old

woodies.

Weather continued to be a problem for the Branford line. A hurricane

in November 1932 flooded out the tracks at Double Beach. A blizzard

in February 1934 interrupted trolley service to Branford and Stony Creek

for several days. Heavy rainstorms on October 18th 1936 and

October 24th, 1937 caused much

damage to beach property and cottages, and washed out the trolley

tracks in several areas. A hurricane struck on September 23rd 1938,

causing considerable damage to the track in the Short Beach meadows. ConnCo

was forced to completely replace the Short Beach bound track there.

Bus Substitution

Throughout the late 1920s and early 1930s, ConnCo was slowly and quietly

replacing its lightly-patronized suburban routes with buses. By doing

so, ConnCo avoided the high maintenance costs associated with a trolley

line, and leveraged the State's investment in road infrastructure which

was being pushed by the increased use of automobiles. In fact, by 1932,

the majority of ConnCo's mileage was being covered by buses, rather

than trolleys.

1932 also marked a low point in revenues. ConnCo was sliding into

bankruptcy, for which the company filed in 1935.

One major contributing cause was their

1906 lease of Connecticut Railway & Lighting (CR&L), the astronomical payments

on which ConnCo had fallen into default. The bankruptcy court terminated

the lease in 1936 and CR&L, for years just a paper company, suddenly became an

operating company again. Within a year they had substituted buses.

One car, number 1330/1333, is preserved in the museum's collection.

Because of the bankruptcy, permission of the court was needed

in 1936 for ConnCo's plan to substitute buses between Branford and Stony

Creek. The plan was approved, though a backlog of new bus orders delayed

the transition until March 1st, 1937. The trolley was cut back

to its 1900-1906 terminus at the Branford Green.

ConnCo would gladly have abandoned the entire Branford line at this point,

but they were blocked by the fact that the bridge that carried State Route

142 over the East Haven River was not adequate to handle bus traffic. This

being the only available road route to replace the private right-of-way

which is now the museum's line, bus substitution had to wait until the

bridge was upgraded. It was by this stroke of luck that the museum's

line would be preserved and become the oldest continuously-operated

suburban trolley line.

Thanks to James M. West, Bill Young, Prof. George Baehr, Roger Steele

and Jane Bouley for

contributing to this article, as well as, posthumously, to Richard

Fletcher who conducted much of the original research.

In our next and final installment,

the railway is saved!

The Shore Line Trolley Museum

17 River Street

East Haven, CT 06512

(203) 467-6927

[ Home ]

[ About The Museum ]

[ Donate! ]

[ The Collection ]

[ Membership ]

[ Guest Operators ]

[ Volunteer ]

[ Site Map ]

[ Members Only ]

This material is copyright © 1997-2020 Branford Electric Railway Assoc. All rights reserved.

Last Updated: /articles/bery100p3.in modified at Thu Mar 10 23:25:39 2005

Comments-To:

[email protected]